My name is Lindsay Jesperson, and I'm excited to share my experiences and some of the strategies that have helped me navigate this age of accelerated digitization and uncertainty.

I’m going to talk specifically about the transitional and seismic shifts that have happened in my career that have led to periods of uncertainty and ambiguity, and how we deal with that as FP&A and finance professionals.

I’ll also share the strategies that I've found are most effective in leading your businesses, your teams, and yourselves personally.

- Helping businesses navigate uncertainty

- Experiencing the global financial crisis at General Electric

- Dealing with seismic shifts in the media landscape

- Revenue transformations in the film industry

- 3 key strategies for handling change and uncertainty

Helping businesses navigate uncertainty

We're always in a period of digitization that we can't control and will always be evolving, but what we can control is that perception of acceleration and uncertainty.

I started my professional career in banking and have held multiple roles in both strategic and operational finance, with responsibilities across film and television, both on the production side and distribution, and nearly always on a global scale. I’ve worked for Comcast, Disney, Bloomberg Television, Viacom, CBS, and GE.

The interesting thing that ties all of my roles together is that I've always come to them during a period of change.

I started at NBC to integrate the universal acquisition for the global film distribution business. At CBS, I replaced a leader who was retiring after 30 years and the business was ready for a new change. And then I went to Disney to help the division president with new initiatives to take ABC News in a more digitally focused direction.

As finance functions broaden with our greater responsibilities, we get to play an important role in helping businesses navigate transformation and leading during uncertainty. There are always parts of our jobs that are uncertain and ambiguous, so becoming comfortable leading and operating with this ambiguity is what's going to be critical to our success.

I think we can all attest that finance is a function that only continues to broaden. Our financial insights help drive not only executive-level decision-making, but a full range of how we operate on a daily basis over a business's lifecycle, and then ultimately how that business competes in its market.

Experiencing the global financial crisis at General Electric

I began my professional finance career at General Electric (GE) in 2003. The company was at the top of its game at the time and sold everything from medical equipment, jet engines, appliances, plastic pellets, film and television shows, and industrial products. It also had its own financial arm for both commercial and personal banking.

I was lucky enough to be on the financial management program, which was an entry-level development program for analysts to be dropped into various operating units, given exposure to all areas of the finance discipline, and serve as its pipeline for future CFOs and finance executives.

In January 2005, I was a young 20-something analyst/ It was my second rotation, and I was lucky enough to be at the global headquarters where the personal banking unit was. This unit handled credit cards, home equity, lines of credit, and mortgages.

It was a classic FP&A role and one where my analyst responsibilities were to collect and consolidate metrics for the division. In this case, as part of the mortgage metrics collections, I was to start tracking the foreclosed or repossessed houses worldwide.

Our story begins with five houses.

As any good FP&A analyst does, I’d set up my spreadsheet template, sent it out with instructions, got it back from all the business leads, and in January, I presented the five houses globally to my manager. Great, job done.

In February, I had to repeat the task, and the number of houses had increased fivefold to 25. I submitted the houses to my manager and was immediately called into his office. He spoke to me about the importance of accurate data, how it looked simple but was crucial for decision making, that this data was going to be seen by the CFO and CEO, and it was going to be reported on the GE annual report, etc.

He’d assumed that I hadn't collected the data correctly and I’d missed responses the first time. I promised to do better and was sent back to my desk to double-check the data again. And of course, all the answers came back confirmed.

In March, I was asked to do this a third time, and 127 houses came back. And this time, my manager was much harsher. He said that I couldn't be trusted, I clearly didn't understand the ask, and anything in finance probably wasn’t the right career path for me. He’d be taking this task away and doing it himself next month.

April came in at 630 repossessed houses. And to this day, I've never seen anyone look quite so horrified and scared as my manager did on that day when he compiled the data and saw the subtotal for himself. And of course, there was a huge panic and a lot more conversations well above my paygrade.

But that was the very beginning, at least for me, of the global financial crisis, and my first taste of massive industry disruption in my career.

The funny conclusion to that story is fast-forward to eight months, in my final rotation, I was sent to Watford, UK to help with the country-level mortgage business. Those few houses that were on that first report became a giant box of keys. It was kept in the pricing manager's office because they quite frankly weren't sure what to do with it.

As you can imagine, the realization set in that in every office in every region, and every too-big-to-fail bank was a similar box of keys representing the houses and families impacted. That shifted my scale of understanding what it was like to be in a business that was going through uncertainty and ambiguity, what that was going to mean, and how it was going to impact me on a day-to-day basis.

But that's not the end of the story. That's just the beginning.

Dealing with seismic shifts in the media landscape

When I finished the rotational program, I was at a crossroads. Did I stay in seismic shift number one in banking and potentially spend the foreseeable future digging out of that financial market meltdown? Or was this an opportunity to pick an industry and change paths? To take this opportunity at the crossroads to potentially do something more fun, exciting, and stable?

So with that, I switched divisions and shifted my career into media at NBC Universal, which was still owned by GE at the time. And what I didn't know was that I was trading a seismic shift in one industry for another.

What I hadn't yet realized was that there were always going to be seismic shifts regardless of what industry you were in. So I very confidently rolled into seismic shift number two.

In this next case, I wasn’t that analyst collecting the exact data at the exact moment to indicate another massive, impending global collapse. That would’ve been too much of a coincidence. The seismic shift was much slower and disruptive in different ways and far-reaching on a different scale.

This seismic shift that was happening in media was playing at a much slower pace, luckily for me. But if you remember, back in 2006, a few things were going on. Piracy was on the rise, which meant you could get a pirated DVD on Tottenham Court Road for $5. They were selling them out of their backpacks when the original was still on the high street shops for nearly five times the cost. That was an indicator of some of the new formats that were becoming accessible, and this posed an increased risk.

The second thing that was happening was that technology was massively improving in terms of quality. We were shifting from HD to 4k quality, and the rise of connected TVs in the form of OTT (over-the-top television) was also being launched and integrated into people's homes.

That also led to the rise of SVOD, or subscription video on demand, which provided viewers with an on-demand alternative to linear and cable offerings.

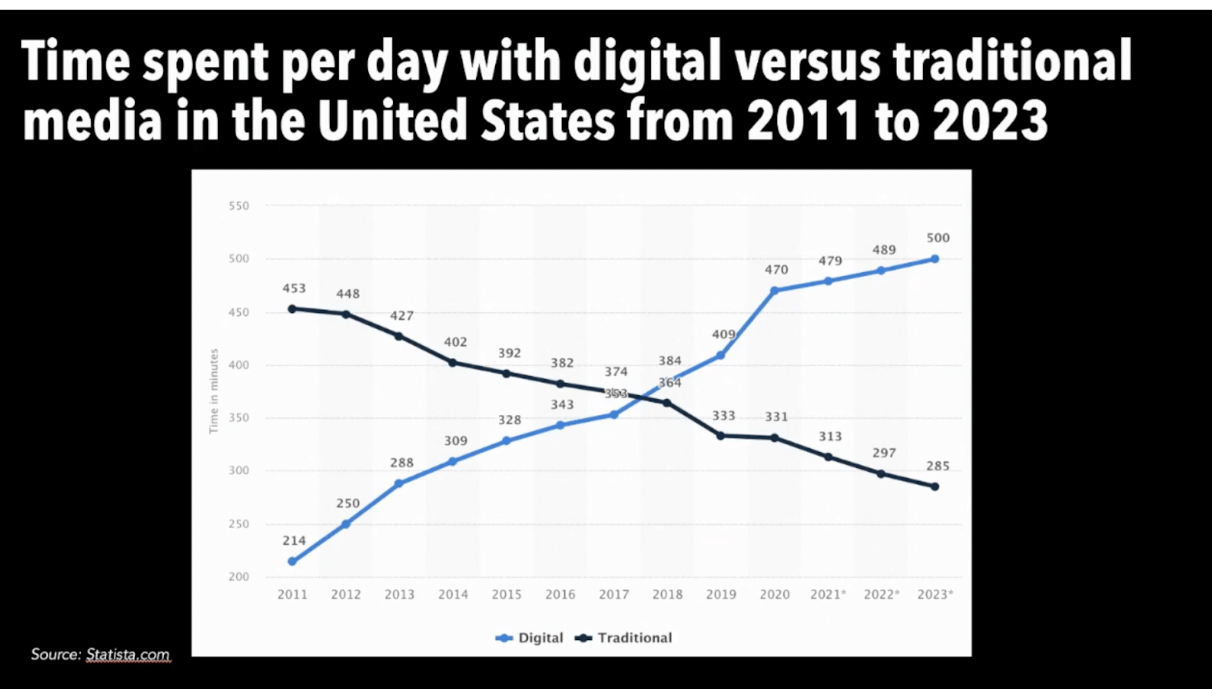

My company had announced a little joint venture at the time called Hulu. The genesis of that was that the recognition of this early data, similar to those repossessed houses, was showing that the traditional analog dollars were being traded for digital pennies, as it was called.

The fact that this trade-off was happening was going to have massive implications for how the business functioned and where the revenue was coming from, so we needed to start shifting what we were going to do about it.

But back in 2006, we were a little early. Or were we? Like those repossessed housing metrics being indicative of larger cracks, these early warning signals were actually being planned for and thought about.

As we fast forward 10 years to 2016, in hindsight, audiences were shifting away from traditional linear and cable broadcasts, and increasingly moving to digital platforms.

In real-time in 2022, this seismic shift is still going on. We're still living through it, and there's still a lot more happening.

But what does this mean for media finance professionals in real-time? It means that the whole model of how you forecast for studio business has changed. It changes the way we plan for our film slates. It changes how we go to market. It changes how we make money, and that's also how we spend money, and how we bring those film and television products to market in their production.

So what does that actually mean? And what does that really look like?

Revenue transformations in the film industry

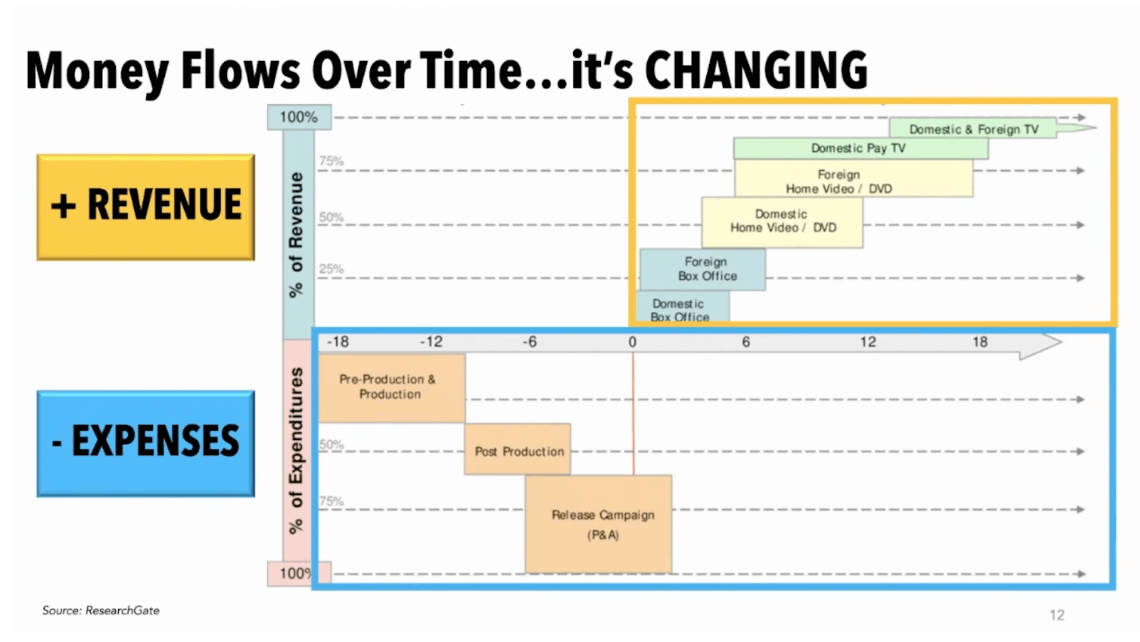

When you think about a film process, the previous lifecycle started off as a seed of intellectual property (IP). Usually, that's in the form of a book, a novel, a graphic novel, or a comic book series. They go through a development process, get produced, and then once the film or films are ready, they get distributed out into the different markets.

Previously, films would traditionally make the most money in their first theatrical windows. This would usually be in the box office when you’d go domestically on the US side or internationally.

In those pay theatrical windows, they’d go on to have a wider distribution, usually on what's called the pay one or pay two window. That’s when those films go on to an exclusive service, then onto a television network, and then possibly onto a DVD.

You could previously estimate the popularity of a film or similar ones to it, and use that to determine how much you're going to spend on the next one based on that box office performance. That could drive how much money you spend actually producing the film and how much you're going to market it next time.

And as you're building up those bigger slates to have all those individual pieces, you have a very clear idea of what the next few years of the business look like.

That's massively changed.

Now those windows have shrunk. In some cases, films aren’t getting released in theatrical windows at all; they're going directly to platforms. It's caused a massive shift in how the revenue is accounted for, and therefore how we're going to think about building up a slate production spend, marketing spend, and distribution spend.

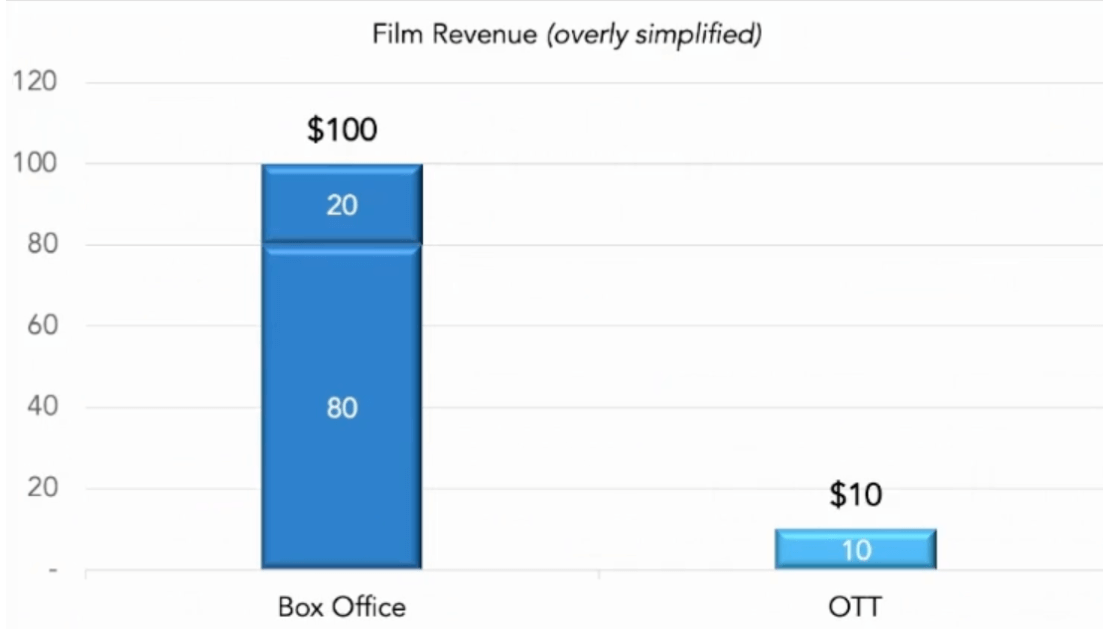

Below is a very simplified example of what I'm talking about, this shift that’s happened now. You can also say that's been accelerated by the behavioral changes from the pandemic.

In terms of what a film previously earned, let's say a family of four went to a theatre, that's about $80, plus $20 for concessions. So in that window, that’s $100 to see that film.

That same film is now being watched at home by that family of four for around $10 a month. That's probably also being allocated based on all the services and things that they're watching, depending on which studio it is.

Going from $100 to $10 has a huge impact. To make the same high-quality films and television shows, you're not necessarily going to drop your production budget from 100 to 10. A Marvel film isn’t going to get made at 1/10 of the cost, nor are you going to be able to market or even distribute it on that platform.

So media companies are now grappling with the fact that we need to overhaul all of the production, marketing, and distribution plans to support what feels and may look like a very similar product, but that has very different revenues attached to it now.

Yes, these revenue models may be overhauled and these pricing ideas might be changed. But there's a massive shift that’s impacting how this business is thought about and is going to continue to change how these businesses are thinking about it going forward.

This seismic shift plays out over a much longer period of time, mostly because media assets always have a runway of a few years. So with the things that are happening now, we're not going to see many of them play out for the next few years.

But stay tuned because this shift hasn't fully happened. There are going to be lots of changes coming in the next few years that are going to be impacting what this is.

3 key strategies for handling change and uncertainty

So where does that leave us? What did we learn from these stories? And what are you going to take with you to navigate change and uncertainty in your own worlds?

I thought about this from three different perspectives: you as the business professional, you as the FP&A leader, and you as the CEO of your own career. It's important to remember that we all wear many hats, and to be effective at strategy, you need to consider the problems and the impacts from multiple perspectives.

So I've distilled it down into three key strategies:

Tackle it head-on

Uncertainty and ambiguity are everywhere all the time. There are always going to be seismic shifts in your industry and your work.

In an alternative universe, maybe I’d still be a banker, and maybe it wasn't all that I feared. But my point is that avoidance isn’t always the best option, and it's not the only option. It’s best to consider other alternatives.

You've already been living with uncertainty and ambiguity, and you've probably gotten quite good at it. We survived the global pandemic, but how did you survive? You adapted to the information you had. If you didn't think you had it before, you probably have a very high tolerance for ambiguity now.

How did you learn to cope? It probably came down to what you chose to pay attention to and how you chose to react to it.

In our FP&A lives, we're never going to have all the answers or all the details. For 20 years of my career, I've always heard, “But what if it changes next week? How are we going to know what's going to happen 12 months from now?”

It's not about being absolutely precise. We can all pull out budgets designed at the end of 2019 and laugh about how far off they are from what actually happened. But it's about thinking about the information now to make your best guess and quantify it.

Of course it's going to change tomorrow, and of course something new will happen. That's one of the fun parts about what we do. It's not static and there's always going to be a business change.

But at the time of publication, what was the most thorough, most accurate, most thoughtfully based plan that you could come up with based on what was reasonable at the time?

It's important to think about those plans and decide on those strategic plans to take them all into consideration.

Don't be surprised. Be prepared.

The best finance and FP&A professionals are the ones who are great at understanding the strategic planning part and the operational execution.

We're in a lucky position to be able to critically think about these KPIs, look at early warning cracks that show up, pay attention to them, and scenario plan for what it’ll mean for your business and yourself personally.

And then what are you going to do about it today to be able to handle that tomorrow?

The first step is to not deny it or procrastinate. Don't put it down. The best way I've heard it described was from one of my favorite strategy professors at London Business School, Julian Birkinshaw. His suggested approach is a phrase that I really like, which is, ‘Be paranoid and pragmatic.’

Operate like you feel like you're being threatened and figure out what you're going to do about it. And the pragmatic part is to deal with it sensibly and make realistic plans.

We see this on every FP&A person's favorite sensitivities page of risks and opportunities. What impact does the issue have on the revenue, cost, net income, and overtime? Is it 50%? Is it 80%? What’s the likelihood? Does that have a probability attached to it?

When you scope out the magnitude and think about those assumptions that drive it, you're actually deconstructing that complexity and making it more certain.

From a leadership perspective, talk to people, socialize the ideas, share those perspectives, and make sure you're helping to future-proof your business by ensuring that teams are prepared and have their game plans ready. Having a plan and really thinking about the ‘what ifs’ and the details is crucial.

In real-time, you might not be able to execute it precisely. But you do need to be flexible and spontaneous to make decisions on the fly, except they're not on the fly if you've thought about them ahead of time. There are always going to be factors that guide you differently. You're not getting graded on perfectionism. It's the planning and consideration that’ll make sure you have a successful outcome.

And on the ‘be prepared’ side, make sure you're ready for what's next, whether it's your next job, a lateral move, a promotion, an external opportunity, or a new industry.

Nobody’s going to tell you, “Hey, there's an amazing opportunity coming your way in six months. Make sure you're ready for it.” You need to be ready now. You need to be expanding your skill set, operating at that next level, and proving to yourself, the hiring managers, recruiters, and interviewers that you're ready and practiced in whatever will come next.

That’ll improve the likelihood that you'll not only get that job and be hired but also improve the likelihood that you'll be brilliant at it.

Find the upside

Not all uncertainty is bad. Not all transformations are bad.

I'll tell you a quick story that's close to my heart. When I was at CBS in London, we were asked to execute a round of layoffs. It was a small office, so everybody knew about the confidential layoffs that were coming.

I had one employee on my team who was nearing retirement age. She was utterly grief-stricken about what was going to happen to her, to the point where she’d cry in the office in absolute fear of the potential dreadful outcomes and was unable to contemplate anything that would be more positive than those.

It was really hard for all of us to see. Our hearts were breaking for her. But nobody could do anything to comfort her, and I couldn't tell her about anything that was coming yet.

But what happened was that her redundancy package was large enough that she paid off her mortgage on her house and filled up her savings account. We’d structured it so that we could offer her part-time project employment to help her make ends meet.

She politely declined because she decided that she'd be spending the next several weeks traveling, and then being busy with her new language classes. She didn't know if she could fit in our part-time offer. Talk about a transformation. I’d never seen her so ecstatic.

So what's the lesson there? Don't get stuck in just one perspective. Keep your mind open, get other people's input, and consider the alternatives.

Sometimes it's easy for all of us to go into the death spiral thinking, and there are probably lots of folks around you who’ll be happy to commiserate and reinforce that. But always remember that there's another way and there might be another end to this story or different paths that you can take.

You might not see it immediately. It might be hard to get to. But that’s fine. You've done hard things before. But your job now is to think about what makes that alternative true and realistic.

The hardest part is forcing yourself out of that death spiral thinking and coming up with alternatives. That’s what's going to increase the likelihood of your success.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn